The heavyweight division in boxing is now stronger than it has been in the past two decades. Between Anthony Joshua, Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury, boxing’s flagship division finally has a trio of heavyweights comparable to Lennox Lewis, Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield, who reigned at the top of the division in the 1990s.

There’s one problem, though: these top heavyweights aren’t fighting each other.

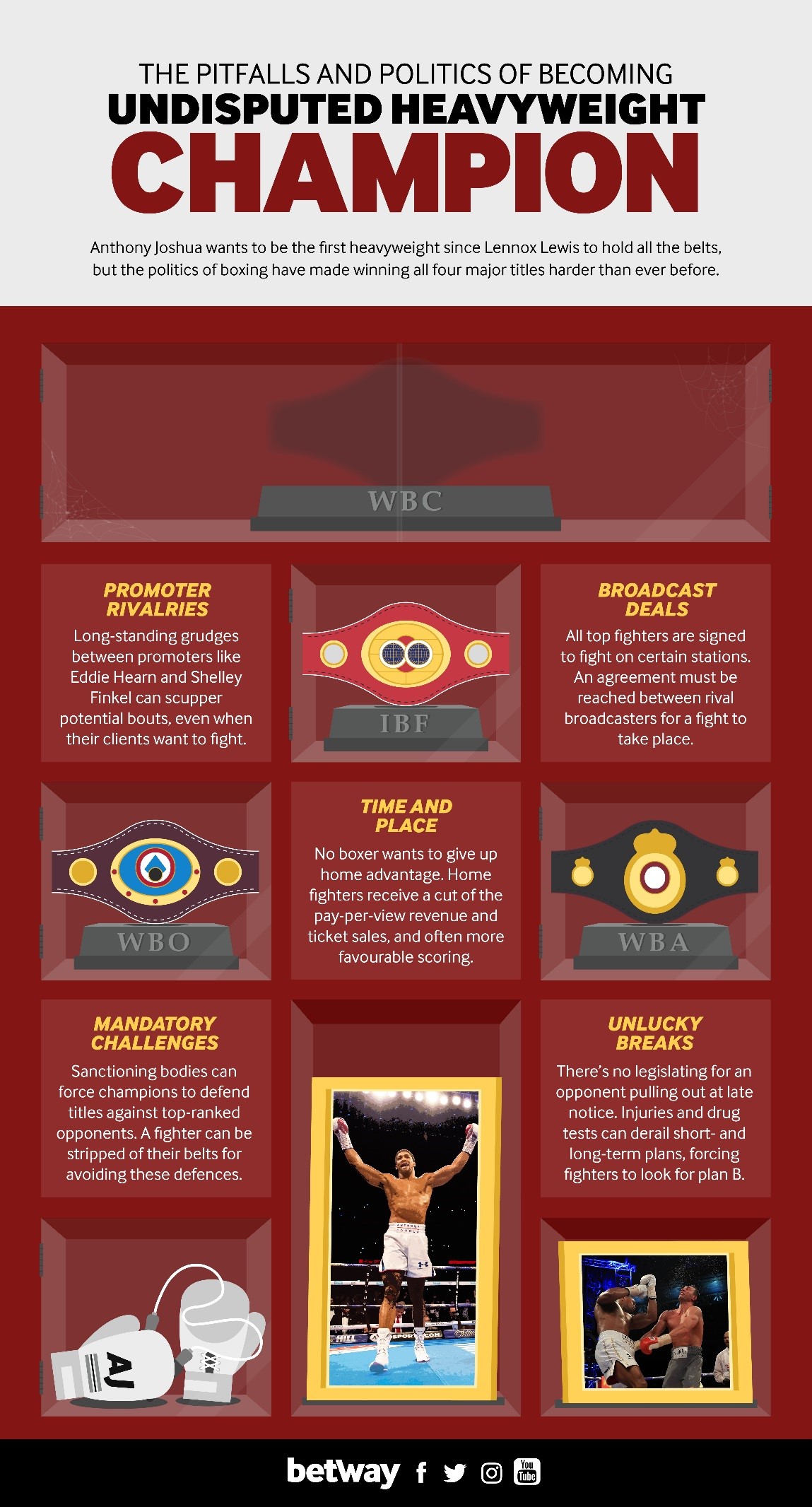

When Joshua – the reigning WBA, WBO and IBF champion – defends his belts against Andy Ruiz Jr at Madison Square Garden on 1 June, much of the focus will be not on the title defence. What boxing fans really wish to see is a meeting with WBC champion Wilder. This would provide Joshua – who is favoured by boxing betting sites like Betway by as much as 33-1 to beat Ruiz – a chance to fight his equal and fulfill his goal of becoming the undisputed world champion.

But chasing the WBC title belt proved to be extremely difficult for the 2012 Olympic gold medalist.

The reason for that is there are now more obstacles involved in unifying the world titles and putting together huge fights than ever before.

For a fight between Joshua and Wilder to be made, their respective promoters must come to an agreement. But negotiations between Eddie Hearn and Wilder’s manager Shelley Finkel have become public and personal over the past two years, with Hearn referring derogatorily to his counterpart as ‘Shirley Winkle’.

It’s common for long-held grudges between promoters who have often been in the sport for decades to jeopardize fights. The financial benefits of staging a contest – namely a greater share of pay-per-view and ticket revenue, and the ability to secure sponsorship deals on top of that – are a clear incentive for promoters to do all they can to hold the upper hand. They also decide where the fight will be staged, the size of the ring and even minor details such as which fighter will take which dressing room.

But boxing agent Tim Rickson, whose clients include former British and Commonwealth middleweight champion Tommy Langford, says promoters unwilling to cede ground to their rivals can also get in the way of their own fighters’ interests.

“It’s business, but a lot of ego comes into it as well,” says Rickson, who is also the editor of British Boxing News. “That power play comes into it where they’re trying to be the biggest promoter with the biggest backing and the biggest fan base.

“Often the fighter is willing but then sometimes the conflicting promoters’ interests – and now the bigger problem, which is the TV broadcast deals – can result in the fight not being made.”

Indeed, the broadcast boom has created another obstacle for these super-fights to overcome.

There’s more money available than ever before for boxers who sign exclusive deals with broadcast companies. In February 2019, Tyson Fury signed a five-fight, £80m American broadcasting contract with ESPN, following in the footsteps of Joshua and Wilder, who have similarly valuable deals with DAZN and Showtime, respectively.

With the big three now all tied up with separate stations, negotiations look close to unworkable.

“It’s so fragmented that it’s just going to be extremely difficult to bring any of those three together,” Rickson says.

“If you’re ESPN and you’ve put £80m into a fighter, you’re not going to let him have a rematch with Deontay Wilder on Showtime.

“Will ESPN say they will step down to let Showtime put it on, or vice versa? No.

“They both want the fight, they have both paid for the fight, they both deserve the fight. They aren’t going to give up their rights to profit from it.”

Rival broadcasters have occasionally found common ground in the past. For example, when Floyd Mayweather fought Manny Pacquiao in 2015, HBO and Showtime aired the bout as a joint production – the first collaboration between the networks since 2002. However, the protracted negotiations pushed that fight back five years later than when it should have taken place – when both competitors were in their primes. Pacquiao had lost twice since negotiations first began in 2009, meaning his decision loss to Mayweather failed to answer the question of which fighter was truly the best at their peak form.

That is always the risk with super-fights: the sheer scope of negotiations that must take place can push the event further and further down the line, until its relevancy is lessened and many of the fans lose interest. But there’s also an incentive for promoters to keep their fighters away from dangerous opponents for as long as possible. Allowing the hype around a fight to build only increases its financial potential, and allows fighters like Joshua and Wilder to remain undefeated for longer.

That latter point is more important now than ever, as defeats are more damaging than they were in the past. It’s what Rickson refers to as “the Mayweather effect”.

“I think Floyd Mayweather is to blame in an indirect way,” he says.

“There’s this new influx of casual boxing fans who only get up for the big fights and aren’t really purists.

“When a fighter gets a loss on his record he is now almost dismissed, which is absolutely nonsensical to a hardcore fan.

“It’s that Mayweather effect – promoters don’t want their fighters to take a loss because they could be dismissed and lose a big following, which would result in fewer tickets sold and fewer pay-per-views.”

There are other risks that delaying big fights can incur. One of them is mandatory challengers. Sanctioning bodies can rule that their top-ranked challengers have earned a shot at the title, forcing a champion like Joshua to defend one of his belts or be stripped, and preventing him from fighting for a new title.

There’s also the sheer luck factor. You can’t account for injuries incurred in training, or opponents failing drug tests that force them out of fights. That’s something Joshua and Hearn have dealt with in recently with Jarrell Miller – who was meant to be Joshua’s opponent on June 1st – testing positive for banned substances and being replaced by Ruiz. Then there’s the chance that the prospective opponent will lose a fight before a deal is done, a fate Joshua nearly suffered in December 2018 when Wilder scrapped to a controversial draw against Tyson Fury.

Should Wilder’s rematch with Fury take place before Joshua gets his shot at the WBC champion, there’s a good chance it will be the Gypsy King – not Wilder – that Joshua will have to beat to win that final belt. That would require Hearn to negotiate with British rival Frank Warren, with whom he is even less likely to strike a deal than Finkel. Or, Joshua could lose on June 1st, leaving Ruiz as the man with three belts, chasing the fourth. As unlikely as this scenario seems, stranger things have happened in combat sports.